Peatlands – a solution to transform our food systems

-

Peatlands

Agriculture faces a unique challenge in the context of climate change. While it itself is vulnerable to fluctuating temperatures and extreme weather events, it is also one of the biggest contributors of greenhouse gases. Directly, farming activities like cattle rearing and the use of synthetic fertilizers release methane and nitrous oxide into the atmosphere. Indirectly, the conversion of biodiverse landscapes into farmlands strips ecosystems of their natural ability to sequester carbon and alters the carbon cycle. In fact, land-use change accounts for nearly 20% of all global anthropogenic emissions.

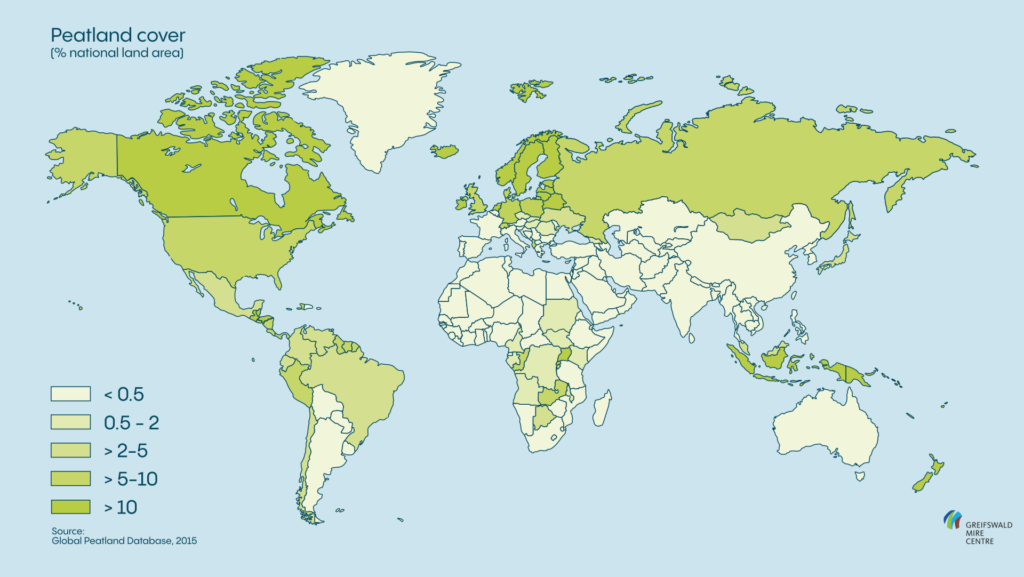

Peatlands are wetlands with a thick water-logged soil layer made up of dead and decaying plant material. They include moors, bogs, mires, peat swamp forests and permafrost tundra. Peatlands are some of our most significant allies in abating the effects of climate change. They are the planet’s biggest terrestrial carbon store, permanently locking it up as long as they remain wet. Despite only covering 3% of earth’s surface, they store more than twice as much carbon as all the world’s forests.

They also play an important role in regulating the hydrology of their surroundings. Their sponge-like qualities allow them to hold and release water gradually, reducing the risks of both droughts and downstream floods – two disasters that are increasing in intensity and frequency due to climate change.

Drainage is the biggest threat to peatlands and about 15% of the world’s peatlands have been drained for agriculture, forestry and grazing. Unlike deforestation, which causes one-off and almost immediate emissions, the emissions from drained peatlands can continue for decades and even centuries.

Wet peatland soils have historically been viewed as waste lands but the production of commodities at an industrial scale has led to the conversion and drainage of peatlands for large-scale palm oil plantations, timber, pulp and paper, fibre and livestock ranching, making them extremely fire prone.

But there is a way to use peatlands in agriculture – paludiculture.

Paludiculture is the productive land use of wet and rewetted peatlands that preserves the peat soil and thereby minimizes greenhouse gas emissions. With paludiculture, peatlands are kept productive under permanently wet, peat-conserving and potentially peat-forming conditions, thus providing a win-win-win situation: the carbon stock is protected, livelihoods are secured, and the ecosystem functions maintained (flood, drought and fire risk reduction). Whilst there is a good understanding on the opportunities that paludiculture can bring, this has not yet resulted in commercial adoption and the development of supply chains, which are crucial to move to large-scale adoption.

Researchers at Wetlands International, the Greifswald Mire Centre and elsewhere are developing and promoting ways of farming with paludiculture. In July 2022, we took German parliamentarians to see an EU-funded project near Malchin in Northeast Germany, where farmers cultivate Typha, a flowering wetland plant also known as cattail or bulrush, which can be sold to make construction materials such as boards and insulation. Other potential high value paludiculture activities include harvesting peat moss, for use in horticulture as an alternative to mining fossil peat, and herding water buffalo. The parliamentarians concluded that such commercial wetland activities could be vital in meeting targets for conserving and rewetting peatlands to be set by the new EU Natural Restoration Law. Paludiculture may not feed the world any time soon, but it offers good bankable reasons for protecting and restoring our wetlands.

Wetlands International also supported communities in Indonesia to develop sustainable rural business models that marry protection of the peatlands, their carbon and biodiversity, with strong livelihoods. Growing sago on peatlands instead of oil palm was suggested to support high water tables, prevent carbon release, and reduce risk of fires. The sago provided food, and the waste could be fed to ducks. To stimulate investment and upscaling of paludiculture in Indonesia, we initiated a platform that facilitates this exchange between stakeholders including between plantation companies, research institutes, governments and NGOs.

These are just some examples of promising pilots that can be scaled up to have far-reaching impact.