The secret to Africa’s drylands is the wetlands? What prospects for future food security?

-

Climate and disaster risks

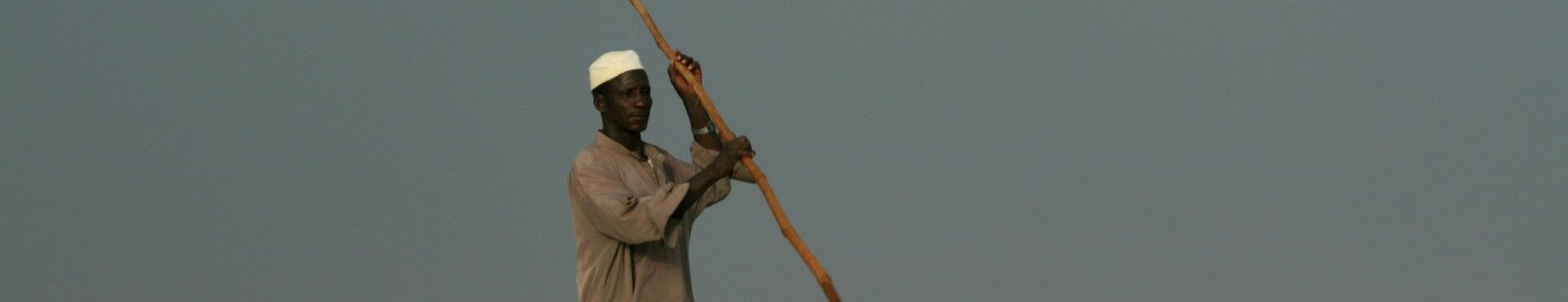

When you think of the Sahel in Africa, what picture does it conjure up? Dry sandy areas with scattered trees and perhaps hungry-looking children looking after cattle and goats? Maybe fewer of you imagine big river systems, heaving with fish, and lined with flooded forests? The magic of this zone, which stretches across Africa and borders the Sahara, is that it is both very dry and very wet. And that nature and people depend on both the drylands and wetlands and move in-between according to the seasons.

Wetlands bordering the Senegal, Niger and Nile rivers, and other smaller rivers, are a lifeline for all in the Sahel. In the dry season, cattle are brought from the desert into floodplains to graze them on floating Bourgou grass, which are a rich source of nutrients. The drylands serve as pasture during the rains. The wetlands are the main water sources for people. Different products are traded between zones, with herders from the drylands exchanging their milk for fish from the wetlands. Farmers rely on annual floods for floating rice cultivation and fishermen cast their nets for fish in the wetlands and ponds. Hippopotami and countless freshwater fish species and hundreds of millions of migratory birds also thrive here. Near the rivers, forests are thicker, sustained by seasonal floods. These flood forests are so valuable to people, they are often known as “local banks”. They are havens for birds whose droppings fertilize the waters so as to make them the most productive for fish, including the highest-value species. Although much of the flood forest has been recently cleared, many communities are now keen to nurture their recovery and reap their rewards. The knowledge about valuable tree species is still held.

Across the Sahel, increased pressures for grazing and cutting of branches for fuel is gradually fragmenting the savannah woodlands and depleting the soil, opening the way for the desert’s spread. But by enabling groups of local women who live alongside the inner Niger delta in Mali, we managed to accomplish something that was deemed impossible: by planting trees and protecting water sources, these women managed to turn the desert around their village into productive land. By adopting new farming and cattle grazing techniques, natural vegetation could re-establish and once more provide nutrients, moisture and shade to the vulnerable crops. These groups established food banks, and saved money, allowing the village to deal with periods of scarcity. Within a matter of years a remarkable transformation took place. In the same way, big areas of floodplain forest have been re-established and is now protected by local communities.

It seems to us that helping communities to help themselves is the most sustainable way to bring about change. Working with regional banks, we have connected communities to a micro-credit scheme that aims to support activities such as trying out new agricultural techniques, improving product marketing or establishing small shops. In return, community groups undertake to stop over-fishing or hunting waterbirds and to help the regeneration of flood forests, swamps and grasslands. Our dream is to extend this across the Sahelian region, to aim to create and resource a growing movement, spreading the work to millions of people, using the power of human-to-human interactions and inspiration to build the small-scale acts of individuals in one place into large-scale changes over time.

We share this dream with many of our environment and humanitarian partner organisations and we are looking for resources that will enable us to turn this into reality. At the same time, we are trying to influence the major investments which threaten to deny this dream. In particular, in the Upper Niger Basin, further diversions of water for upstream irrigation and hydropower operations could worsen drought conditions by limiting the extent and duration of seasonal floods in the inland delta each year. This effectively would cut off the food and water supply for around a million people. In the driest years, this turns into a humanitarian disaster. Such disasters are predicted to become more frequent in the Sahel. Principally because of these development decisions, not because of climate change.

So, while increasing food production through irrigated agriculture and hydropower are clearly part of the solution to meet increasing demands for food and energy in this region, there is a need to see the bigger picture and what’s at stake. To explore some additional options. We are convinced that there is a strong case to safeguard seasonal water flows that sustain the Sahelian rivers and floodplains – and to enable rural communities to take action locally that will increase their own food security and enhance their well-being, while maintaining nature. This is why Wetlands International and its partners are seeking to influence the development agenda to make sure it includes investment, not only in traditional water-intensive food and energy solutions, involving major hard infrastructure schemes, but also investment in sustaining and restoring wetlands as “natural infrastructure”.

Linked with World Wetlands Day, we are bringing together tomorrow, Monday 3rd of February, around a hundred guests from business, government, knowledge institutes and NGOs for an evening in The Hague where we will deepen the dialogue on this issue. We will share examples of exciting initiatives and exchange perspectives on the opportunities and challenges to scale up investments in wetlands as natural infrastructure. We will call for greater action, through collaboration, to achieve this.

The impact we have had to date would not have been possible without our partners, members and donors, but we need to do more. We are now recruiting individual and corporate supporters and seeking flexible funding that will enable us to respond effectively to meet current challenges and opportunities. If you would like more information on how to help, please email [email protected], or make a donation today.

Read more about our work in the Sahel.