Citizen Science that can change policy

-

International Waterbird Census

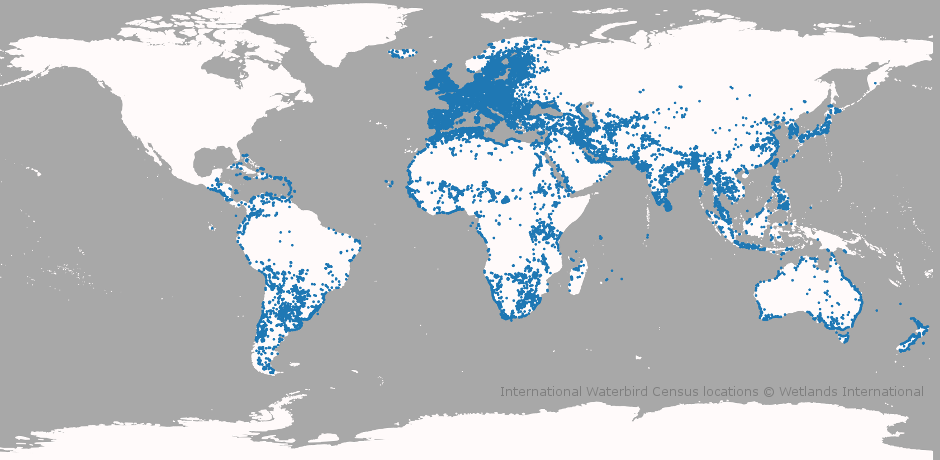

Facilitating knowledge transfer is part of what we do at Wetlands International, and 2017 included one particularly large transfer: having overseen more than 15,000 bird counters for 23 years, we took 2.4 million waterbird records, transformed them into analysable data, and moved it on to academics at Cambridge and other universities.

We helped them process and analyse the data with our computing power, in silicon chips and grey matter alike. The result is an article in the journal Nature which may reshape priorities in conservation practice and funding. The scale of the effort on the (often muddy) ground might well be matched by the scale of impact on policy.

The Cambridge researchers, Tatsuya Amano and William Sutherland, overlaid factors caused by humans, and revealed some truths about conservation since 1990. Human population growth, climate change, agricultural expansion, and surface water change—all are worth considering, but none has the level of impact of one factor: governance. In this case, governance means how effectively a country enforces the rules, according to World Bank indicators. It sounds obvious enough but brings up the kicker of the second most significant, and intertwined, factor: whether or not the survey site is formally protected as some sort of nature reserve, combined with how strong the governance is. A protected area in the European Union normally works better than one in South America or sub-Saharan Africa. So there are geopolitical implications to this study, grounded as it is in the simple, fine pleasure of volunteer birders enjoying a bracing January day out counting waterbirds.

The analysis starts on the premise that waterbird counts can indicate how productive a wetland is; and wetlands are great for biodiversity. So changes in the number of species and of populations can point to changes on the ground. The maps show losses in some areas, growth in others.

Conservation today, certainly as practised by Wetlands International, strives to benefit humans and nature alike. All being part of an ecosystem, it makes sense to seek that balance. We also work cooperatively, providing knowledge and expertise from, for example, ecology and community facilitation, to governments and business. This research collaboration with academia reinforces not just the validity of this approach but also how it must be expanded.

Start with bird counters, organised at the national level; move that data up to the global level; publish in a high-profile journal; and then influence the priorities of decision-makers. The process is much easier said than done, but the potential rewards are there for everyone along the chain.

How do you find 15,000 people to count birds for two decades? For us, that might look like the ‘easy’ part: bird watchers are everywhere and passionate about what they do. In reality though, identifying and counting waterbirds takes a lot of knowledge and experience which is more plentiful in Europe than parts of Africa and Asia. For a global enterprise such as this, finding the people and collating all their records is no small feat. Much of the fieldwork was part of the International Waterbird Census, which has been in operation since 1967 and is coordinated by Wetlands International. While that census does not cover the USA, it dovetails nicely with the comparable Christmas Bird Count run by the National Audubon Society, and the researchers were able to use both together. Our in-house technical officers took charge of these growing datasets, and passed them onto researchers Tatsuya Amano and William Sutherland who prepared the article for Nature along with Tamás Székely and Brody Sande of the universities of Debrecen and Santa Clara. Our staff on this project were Szabolcs Nagy, Taej Mundkur, Tom Langendoen, and Daniel Blanco, who worked with Candan U. Soykan of the Audubon Society.

The data, in the form of the Nature article, will continue its journey: it will inform the continued International Waterbird Census; meanwhile our advocacy and programme staff will take the new knowledge generated by this research and engage, as ever, with governments, business, and civil society to safeguard and restore wetlands for the benefit of people and nature.

Supporters

The International Waterbird Census would not be possible without diverse support, not least from the thousands of volunteers who go out counting waterbirds and sharing their records. Institutional support includes: Ministry of the Environment of Japan, Environment Canada, AEWA Secretariat, EU LIFE+ NGO Operational Grant, MAVA Foundation, Swiss Federal Office for Environment and Nature, French Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, UK Department of Food and Rural Affairs, Norwegian Nature Directorate, the Netherlands Ministry of Economics, Agriculture and Innovation, and Wetlands International members.

The 2018 International Waterbird Census takes place:

Asia-Pacific: 6 – 21 January

Africa-Eurasia: 13 – 14 January

Caribbean: 14 January – 3 February

Central America: 15 January – 15 February

The Neotropics: 3 – 18 February and 7 – 22 July