Hope for Senegal’s blacklisted Ramsar site, Part I

-

Climate and disaster risks

June is the end of the hot and dry season in Senegal. More auspiciously, it is peak mango season. As I drove north from the capital of Dakar with a team from the Wetlands International Africa office, mango sellers blanketed the roadside selling the best mangoes I’d ever tasted.

On my journey to Senegal’s Ndiaël Avifauna Special Reserve, a former floodplain with wetlands of international importance, I started piecing together the decades-long story of the Reserve’s collapse and how Wetlands International and our partners are helping to lay the groundwork for its rebirth. As the kilometres and hours passed by, the mango stands thinned out and the vegetation grew sparser – more goats, more cattle, and more sand greeted us as we entered the Sahel region that buffers the relentlessly advancing Sahara Desert to the north.

We arrived in the Ndiaël after passing over the iconic ‘’Pont Faidherbe’’ and the Senegal River outside of Saint-Louis, the former capital of Senegal and French West Africa. It was hard to imagine in the dust and searing heat of June, but the Ndiaël Reserve was once an oasis of desert wetlands in the Sahel.

Ecological Collapse

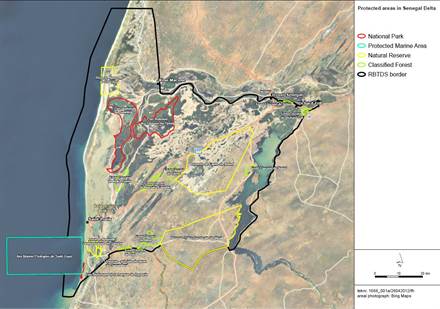

The Senegal River is the second largest river in West Africa and forms the natural border between Senegal and Mauritania for much of its course as it flows west towards the Atlantic Ocean. For generations inundation in the wet season from the river overflowing its banks created seasonal wetlands that supported human livelihoods and abundant fish and birdlife.

The demise of this ecosystem spans decades of natural and manmade calamity. The construction of roads and dams in the 1960’s, 70’s and 80’s cut off the flow of water. Along with a prolonged drought, this created a downward spiral for the environment that has continued until today. Some changes in the floodplain were for the benefit of large-scale agriculture, such as the production of water-intensive sugar cane in the Senegal River Basin around Lac de Guiers, Senegal’s largest freshwater lake and Dakar’s freshwater supply.

Hitting bottom

The Ndiaël Reserve gained worldwide recognition in 1977 when it was designated as a Ramsar Wetland of International importance, in part because it regularly supported at least 1% of the global populations for over 25 species of birds, including the white pelican. But by then the ecosystem was in a state of collapse. In subsequent years, more drought and the closure of remaining water outlets from Lac de Guiers pushed the Ndiaël over the ecological edge and completely dried out the Reserve. In 1990 the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands was forced to put the Ndiaël on the Montreux Record – its blacklist of most threatened sites, where it remains today.

At meeting of partners and stakeholders in the Reserve, I heard a story from Babacar Diagne the secretary general of our community partner, ‘’Association inter-villageoise du Ndiaël’’ (AIV Ndiaël), that put a human face on this tragedy. When the sugar cane company reinforced a dike to prevent any further leakage in the 1970’s, it cut off the Reserve’s lifeblood. In a period of severe drought in 1991, four men, including Babacar and his father Bouna Diagne, desperate for water, dug through the dike with their bare hands. Water soon arrived in their village of Nietty Yone and flowed into the Grande Mare after 72 hours. The police arrested and jailed Bouna and the sugar cane company stopped the flow of water. Rather than stay in their village to die without water, all the remaining villagers, including wives and children demanded to be put in jail as well. The crisis prompted a presidential decree granting the Ndiaël a minimal amount of water, but the subsequent decades have brought mostly hardship for the people, birds and fish here.

The final insult to the Reserve arrived without warning. The government suddenly carved 20,000 hectares of protected area out of the 46,000 hectare Reserve and granted them to Senhuile, a majority foreign-owned company, for large-scale irrigated agriculture. Despite the intense protest of local communities, this was the latest in a long line of water-grabs in the Ndiaël and could have sealed its demise.