Hope for Senegal’s blacklisted Ramsar site, Part II

-

Climate and disaster risks

Despite the long history of abuse, Senegal’s Ndiaël Avifauna Special Reserve remains important, with a huge potential for restoration to benefit both people and nature, and that’s why Wetlands International and our partners have committed to the rewetting of the Reserve for the past five years.

A long way back

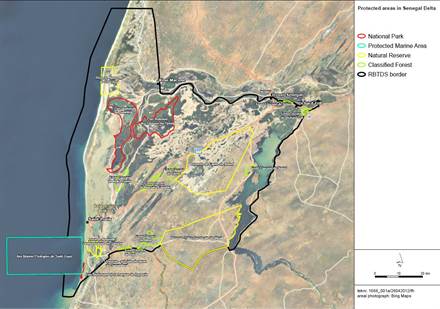

There are strong linkages between the Reserve and other important nearby refuges for migratory birds, Djoudj National Park in Senegal and Diawling National Park in Mauritania. Millions of waterbirds migrate each year along the East Atlantic Flyway, spanning an area from the Russian Arctic to South Africa. These Senegal River Delta sites are the most important non-breeding and resting areas on the East Atlantic Flyway south of the Sahara, with the birds crossing back and forth between the various wetlands.

From where I was in the Reserve, the rainy season was about to begin upstream at the source of the Senegal River in the highlands of Guinea. The seasonal rains from May to October/November used to support an incredible abundance of fish and birds downstream in the Ndiaël wetlands. The fish spawned in July and August on the rising waters. Pelicans and other birds bred from November to January, as the waters receded and concentrated the fish. For decades, however, this cycle of life has been disrupted: no water could make it further downstream than Lac de Guiers and the situation in the Ndiaël remained dire.

Increasing the resilience of communities

Despite the loss of water, small communities have persisted around the Reserve, scraping out a living in their traditional ways in this harsh environment. For the past four years we have worked with local partner AIV Ndiaël, representing 32 communities and 20,000 people. The leaders of AIV Ndiaël had the foresight to recognise that their way of living was not sustainable. The natural environment could not support the growing pressure it faced, with too much wood cutting, too much grazing and not enough water. With the benefit of training to develop skills and capacity, AIV Ndiaël has dedicated itself to both monitoring and restoration activities to better sustain the future of people and nature in the Reserve. Through their waterbird monitoring, AIV Ndiaël now provides valuable data on the different species of birds and their numbers for the annual International Waterbird Census. They are also working to improve the land, excluding grazing from certain areas to allow trees to regenerate, reforesting with local species of trees, and learning how to use the products of these same species, such as fruits and nuts, for sustainable income generation.

Water is life

Everything changed when the first restoration efforts by the AIV Ndiaël were followed by an unusually wet 2010, which created a modest inundation. Suddenly, long dormant Ndiaël wetlands came back to life on a small scale, offering a preview of the abundant birdlife and vegetation it could support. In conjunction with Wetlands International, the AIV Ndiaël communities that had previously lacked the capacity to defend their interests from powerful actors found their voice and pressed for water to restore the Reserve.

In an ironic twist, the next piece of the restoration puzzle came courtesy of an unexpected source. By improving the canal from Lac de Guiers, the agriculture company Senhuile helped deliver much needed water to further resuscitate the Ndiaël – using their influence to push through a project that had stymied conservationists for years. While the activity was clearly motivated by self-interest for their thirsty crops, after being pushed by AIV Ndiaël and Wetlands International to improve their stewardship, Senhuile is at least showing signs of opening up and now says the rewetting of the Ndiaël is a priority for them as well.

La Grande Mare

I heard another story from Babacar when I was in the Reserve that stuck with me: about the days when his father Bouna watched large ships ply the Grande Mare, making their way up the Senegal River from the coast. The 10,000 hectare Grande Mare lies at the heart of the Reserve. It is the centrepiece in our vision for a restored Reserve and for the past 40 years it has been a parched wasteland completely devoid of water. Standing here in June as the heat shimmers off the dry ground, any vision of ships would certainly be a mirage.

But the shells and desiccated frogs under my feet testified to the beginnings of a success story here. Finally, in January 2013, thanks to the work of Wetlands International and AIV Ndiaël, along with partners Altenburg & Wymenga, Birdlife Netherlands, IUCN-Netherlands and BothEnds, water came flowing back into the Grande Mare for the first time in decades. Despite our limited resources, we’ve proven that the restoration of the Ndiaël is feasible. It will never be in a completely natural state again, but with the collaboration of stakeholders it can be managed to mimic the natural water cycle that supports life here.

And this good news is definitely being noticed. The African Development Bank is investing in a large project that aims to build on our track record, making the recovery of the Reserve a high priority. Wetlands International and IUCN-Senegal are helping to steer it and AIV Ndiaël will implement projects on the ground.

At the same time, we are currently guiding the development of a new management plan for the Reserve, with the aim of not only revitalising it for local beneficiaries, but getting it off the Ramsar blacklist and making it an international destination for birdwatchers. The well-attended two-day stakeholder workshop I attended in Ross-Bethio launching this undertaking was proof of the high degree of interest in the Reserve, attracting a swarm of television cameras and journalists from around the country. (Watch a news story – in French).

After many years of enduring worsening prospects AIV Ndiaël communities are suddenly optimistic about the future of the Reserve. I caught a glimpse of what successful restoration will look like – for both people and nature – when Bouna Diagne remarked with satisfaction how good it was to, for the first time in many years, eat fish from the Ndiaël.

More information

Read Part I of this blog.

Read more about our work in Senegal’s Ndiaël Special Reserve.