Turning the tide on threats to waterbirds in the Yellow Sea

-

Species

-

Biodiversity

-

Coasts & Deltas

Since the 1950s and 80s, respectively, 65% of tidal flats and 60% of salt marshes in the Yellow Sea region have been lost. Bordered by eastern China, North Korea and South Korea, the Yellow Sea tidal flats are now considered an endangered ecosystem under the IUCN Red List due to their decline, the severity of their degradation and disturbances such as disease and invasions of exotic species. In parts of the Yellow Sea, there is next to no salt marsh, even in areas where a tidal flat remains.

Salt marshes and tidal flats serve as vital habitats for biodiversity and are critical in protecting coasts against erosion and floods.

So what’s causing their demise?

One of the biggest culprits is land reclamation and embankment: in South Korea, around half of the tidal flats (about 2400 km2) have been embanked since the 1970s, with only a fragmented total of approximately 220 km2 having received protection status. In China, the seawall stretches for 13,830 km along the coast.

The damming of both the Yellow and Yangtze rivers has drastically reduced the sediment supply to the coastline. Water use for irrigation and human consumption in the upper reaches of the Yellow River has also considerably reduced the freshwater flow to its delta. Coastal groundwater extraction is associated with subsidence – downward vertical movement of the Earth’s surface – of up to 25 cm a year.

In China, sewage disposal and the movement of chemical industries to the coast increase the risk of chemical pollution. There are also huge outbreaks of macroalgae such as Ulva prolifera, the branched string lettuce, in China and South Korea. These are thought to be a result of multiple factors, including climate change, rising sea temperatures and eutrophication (a process whereby the environment becomes enriched with nutrients) caused by increased nitrogen pollution.

This is alarming because, especially in recent decades, the loss of tidal flats and salt marshes is impacting species of high conservation concern, including migratory water birds that depend on these intertidal areas.

Coastal areas in the Yellow Sea are threatened by the invasive Cordgrass, a group of grasses native to Atlantic, European and African coasts, which have been introduced intentionally and unintentionally to many coastal areas globally. Occupying large areas of open tidal flats and often facilitating the accumulation of sediment, Spartina can be detrimental to shorebirds, making tidal flats and salt marshes inaccessible to them, as well as reducing the diversity of benthic macroinvertebrates – a type of aquatic animal without backbone which plays a highly important role in the stream ecosystem and are prey for fish, birds and other animals. Spartina can also outcompete native plants, including Zostera, Suaeda, Phragmites australis, and Scirpus mariqueter, decreasing the amount of food resources and nesting habitats for birds. Meanwhile, in provoking the loss of fauna such as shellfish, Spartina can even negatively impact human livelihoods.

The coastline of the Yellow Sea is a critical area for migrating birds and their reliance on this habitat as a migration stopover is a significant reason for their decline. The Yellow Sea stopover accounts for around 40% of the birds travelling on the East Asian-Australian Flyway – a major bird migration route connecting Russia, China and Alaska with South East Asia, Australia and New Zealand – with a yearly influx of around 3 million birds.

In response to human population growth, many coastal areas have been converted to aquaculture ponds for food production, with China being the leading aquaculture producer in the world. Although artificial, aquaculture ponds can in fact provide roosting and foraging sites for shorebirds, depending on how they are managed.

Overall, the coastal ecosystems in the Yellow Sea ecoregion, and the species within, are under immense pressure, but there have been some victories among those advocating for their preservation. In 2018, China introduced strict regulations on land reclamation, whereby general land reclamation projects will no longer be approved, while in South Korea, in 1999 and 2005, Supreme Court challenges led to temporary production stoppages to the construction of the Saemangeum Seawall, the longest seawall-dyke in the world.

Yet, according to IUCN, despite efforts to strengthen protection for habitats in the Yellow Sea, most species continue to decline.

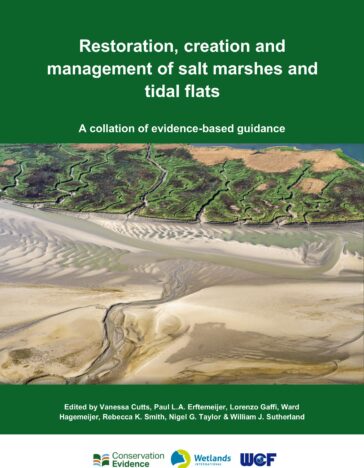

New guidance – produced by Wetlands International in collaboration with the Conservation Evidence Group at Cambridge University – provides a tool to help address some of these challenges. It offers 14 distinct pieces of guidance covering a range of topics and conservation actions, from evidence-based decision-making to specific restoration techniques, drawing on the expertise of 15 advisors from countries including China, South Korea, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, the USA, and the Netherlands. These guidelines are a critical resource and the first of their kind in supporting practitioners and decision-makers with evidence-based best practice guidance for the restoration, creation and management of salt marshes and tidal flats.