Peatlands of South East Asia are heading towards a socio-economic disaster

-

Climate mitigation and adaptation

-

Peatland conservation and restoration

Agricultural production in vast regions of South East Asia will be lost in the coming decades as a result of flooding of extensive lowland landscapes due to unsustainable development and management of peat soils. About 82% of the Rajang Delta in Sarawak (East Malaysia) will be irreversibly flooded within 100 years and substantial areas are already experiencing drainage problems. This will increasingly impact local communities, the economy and biodiversity and will develop over time into disastrous proportions unless land-use on the region’s peatlands is radically changed. Therefore Wetlands International calls for conservation and sustainable management of peatlands in South East Asia.

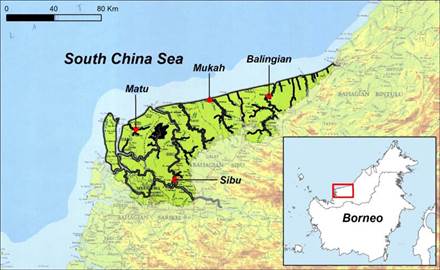

A study commissioned by Wetlands International and executed by Deltares suggests that extensive drainage of peatlands for oil palm cultivation in the Rajang river delta results in such massive land subsidence that this will lead to extensive and devastating flooding incidents in the coming decades.

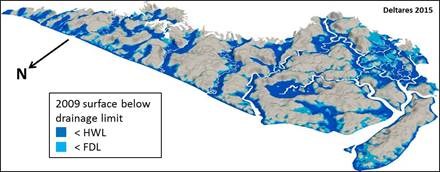

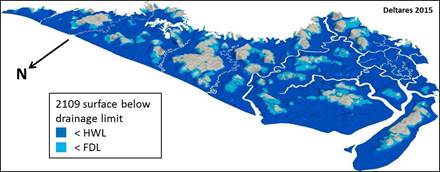

The study analysed an area of 850,000 hectares of coastal peatlands in Sarawak, and produced a model which demonstrates that in 25 years 42% of the area will experience flooding problems. In 50 years the percentage affected will increase to 56% while the nature of flooding becomes more serious and permanent, and in 100 years 82% of the peatlands will be affected.

Such extensive flooding is due to massive conversion of peat swamp forests to agriculture, mainly oil palm plantations: currently only 16% of Sarawak’s natural peat forests remain. These valuable crops require drainage in order to be profitable.

“The results of the model clearly shows the need for a radical change in peatland landuse not only in Sarawak but in all peat landscapes in the region”, said Lee Shin Shin, Senior Technical Officer of Wetlands International – Malaysia.“Current trends whereby vast areas of peatlands are opened up for drainage-based activities will render these areas unproductive and useless and this will adversely impact communities, industries and biodiversity that rely on such areas for their very survival and existence.”

Peat soils are made up of 10% accumulated organic material (carbon) and 90% water. When water is drained from the peat soil, the carbon in the peat soil is turned into CO2 and emitted into the atmosphere causing climate change. This carbon loss reduces the peat volume and thus causes the peat soil to subside. This process continues as long as drainage is continued and until the soil surface reaches sea or river levels constraining the outflow of water and thus leading to flooding. In tropical conditions, peat drainage causes the soil to subsidence at a rate of 1 to 2 metres in the first years of drainage, and 3 to 5 centimetres per year in subsequent years. This results in the subsidence of the soil by up to 1.5 metres within 5 years and 4 to 5 metres within 100 years.

“The study results are very relevant to Indonesia as well, where we observe the same patterns of peat swamp forest conversion, drainage and expansion of oil palm and Acacia for pulp wood plantations”, said Nyoman Suryadiputra, Director of Wetlands International – Indonesia. “Thousands of square kilometres in Sumatra and Kalimantan may become flooded in the same way as the Rajang delta, affecting millions of people who depend on these areas for their livelihoods”.

“Highly developed countries or regions in temperate areas, such as the Netherlands, cope with soil subsidence by building dykes and pump-operated drainage systems, but this is impossible in Malaysia or Indonesia”, explained Marcel Silvius, Programme Head for Climate Smart Land Use at Wetlands International. “The predominantly rural economy along thousands of kilometres of coastline and rivers, combined with the intense tropical rainfall makes it economically and practically impossible to implement such costly water management measures in the Southeast Asian region”.

Governments and industry should therefore immediately stop the conversion of remaining peat forests to agricultural or other use, and actively promote peatland conservation and restoration. Industry will need to phase out drainage-based plantations on peatlands, as these areas will be increasingly subject to flooding and eventually become unsuitable for any form of productive land-use. Effective policies should be drawn up, implemented and enforced to conserve and ensure the wise use of peatlands. There are many crops that can be cultivated on peatlands without drainage. Over 200 commercial local peat forest tree species have been identified, such as Tengkawang (Shorea spp.) which produces an edible oil and Jelutung (a latex producing species). These can provide alternative and sustainable livelihood opportunities for local communities but require piloting, improvement of varieties and up-scaling for industrial plantations.

For more information:

Marcel Silvius

Programme Head,

Climate-Smart Land Use

[email protected]

+31 (0) 318 660910

Bas Tinhout

Technical Officer,

Climate-Smart Land Use

[email protected]

+31 (0) 318 660951